Native binary obfuscation in clang-repl

[TL;DR] Check the PoC and skip to conclusions

Background

Obfuscation is a technique for making code more difficult to understand. It has its origins in source-distributed languages like JavaScript and evolved in close relation to minification since the 2000s.

More recently, mature tools for decompilation and binary analysis have become widely available. 2019 marked a turning point when NSA open-sourced Ghidra. Combined with automation toolkits like Joern, vulnerability analysis for binary-distributed software (and even device firmware) has made great strides. As a consequence, anti-tampering solutions for native toolchains are gaining traction. Obfuscation plays an important role, because it raises the bar for attackers, e.g. to identify sensitive parts in the code through pattern matching.

Obfuscation can be implemented as a post-link step: Lift binary code to an intermediate-representation (like LLVM IR), transform it and lower the result back to binary. Trail of Bits’ McSema and Remill are well-known binary lifters. Meta’s BOLT uses the same approach for post-link optimizations. It doesn’t have to be like that though.

Obfuscation as compiler pass

Compilers run a lot of transformations when they translate source code to binary. We call them passes. There are analysis passes (e.g. reaching definitions, alias, branch probabilities), optimization passes (inlining, loop unrolling), elimination passes (dead-code, loops), allocation passes (registers, stack slots), instruction selection passes (isel, inst-combine) and many more. In clang we can dump them with the -fdebug-pass-structure option – give it a try and if you feel lucky, check -O3!

➜ clang -c hello.c -o /dev/null -O2 -fdebug-pass-structure

The New Pass Manager in LLVM provides a comfortable way for compilers to inject additional passes into the codegen pipeline. We call them out-of-tree passes, because they are not part of the original distribution (unlike in-tree passes that are built-in). Clang provides the command-line option -fpass-plugin and expects a shared library that registers new passes in the transformation pipeline (API docs, LLVM example plugin).

obfuscator.re / O-MVLL

O-MVLL uses pass injection to implement obfuscation at compile-time. It was built by Romain Thomas and got open-sourced in 2022 as a framework to develop, tune and show-case obfuscation techniques. The project is maintained by Build38 and I helped building some infrastructure for it in 2023.

O-MVLL provides a Python configuration API that allows users to select and paramterize transformations for specific use-cases. I added a new API callback recently, that exposes actual IR-level changes to Python. The following script enables the Arithmetic Obfuscation pass and dumps a diff for each applied transformation:

import omvll

from functools import lru_cache

from difflib import unified_diff

class MyConfig(omvll.ObfuscationConfig):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

def obfuscate_arithmetic(self, mod, func):

return omvll.ArithmeticOpt(rounds=2)

def report_diff(self, pass_name: str, original: str, obfuscated: str):

print(pass_name, "applied obfuscation:")

green = '\x1b[38;5;16;48;5;2m'

red = '\x1b[38;5;16;48;5;1m'

end = '\x1b[0m'

diff = unified_diff(original.splitlines(), obfuscated.splitlines(),

'original', 'obfuscated', lineterm='')

for line in diff:

m = line[0:1]

if m == "+":

print(green + line + end)

elif m == "-":

print(red + line + end)

else:

print(line)

@lru_cache(maxsize=1)

def omvll_get_config() -> omvll.ObfuscationConfig:

return MyConfig()

Let’s consider a minimal C++ example with an XOR operation in the printf parameter:

#include <cstdio>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

printf("%d\n", argc ^ 123);

return 0;

}

We can easily see how the obfuscator outlines the operation and replaces it with an equivalent, more complex expression:

➜ clang++ -O1 -fpass-plugin=/path/to/libOMVLL.so -o xor-example -c xor-example.cpp

omvll::Arithmetic applied obfuscation:

--- original

+++ obfuscated

@@ -9,16 +9,45 @@

; Function Attrs: mustprogress norecurse uwtable

define dso_local noundef i32 @main(i32 noundef %argc, ptr noundef %argv) #0 {

entry:

- %xor = xor i32 %argc, 123

- %call = call i32 (ptr, ...) @printf(ptr noundef @.str, i32 noundef %xor)

+ %0 = call i32 @__omvll_mba(i32 %argc, i32 123)

+ %call = call i32 (ptr, ...) @printf(ptr noundef @.str, i32 noundef %0)

ret i32 0

}

; Function Attrs: nofree nounwind

declare noundef i32 @printf(ptr nocapture noundef readonly, ...) #1

+; Function Attrs: alwaysinline optnone

+define private i32 @__omvll_mba(i32 %0, i32 %1) #2 {

+entry:

+ %2 = add i32 %0, %1

+ %3 = add i32 %2, 1

+ %4 = xor i32 %0, -1

+ %5 = xor i32 %1, -1

+ %6 = or i32 %4, %5

+ %7 = add i32 %3, %6

+ %8 = or i32 %0, %1

+ %9 = add i32 %0, %1

+ %10 = or i32 %0, %1

+ %11 = sub i32 %9, %10

+ %12 = and i32 %0, %1

+ %13 = sub i32 0, %11

+ %14 = xor i32 %7, %13

+ %15 = sub i32 0, %11

+ %16 = and i32 %7, %15

+ %17 = mul i32 2, %16

+ %18 = add i32 %14, %17

+ %19 = sub i32 %7, %11

+ %20 = or i32 %0, %1

+ %21 = and i32 %0, %1

+ %22 = sub i32 %20, %21

+ %23 = xor i32 %0, %1

+ ret i32 %18

+}

+

attributes #0 = { mustprogress norecurse uwtable "min-legal-vector-width"="0" "no-trapping-math"="true" "stack-protector-buffer-size"="8" "target-cpu"="x86-64" "target-features"="+cmov,+cx8,+fxsr,+mmx,+sse,+sse2,+x87" "tune-cpu"="generic" }

attributes #1 = { nofree nounwind "no-trapping-math"="true" "stack-protector-buffer-size"="8" "target-cpu"="x86-64" "target-features"="+cmov,+cx8,+fxsr,+mmx,+sse,+sse2,+x87" "tune-cpu"="generic" }

+attributes #2 = { alwaysinline optnone }

!llvm.module.flags = !{!0, !1, !2, !3}

!llvm.ident = !{!4}

The new code doesn’t contain the one single XOR operation anymore. Potential attackers need to invest more effort to uncover it. In this simple case, we can get the same insight like this:

➜ clang++ -O1 -S -emit-llvm xor-example.cpp -o original.ll

➜ clang++ -O1 -S -emit-llvm xor-example.cpp -o obfuscated.ll -fpass-plugin=/path/to/libOMVLL.so

➜ diff -u original.ll obfuscated.ll

But the the script-based approach has a few advantages already:

- If multiple obfuscations are applied, we can see each individual step and not only the sum of all transformations.

- We can enable/disable/fine-tune subsequent obfuscations based on actual transformations.

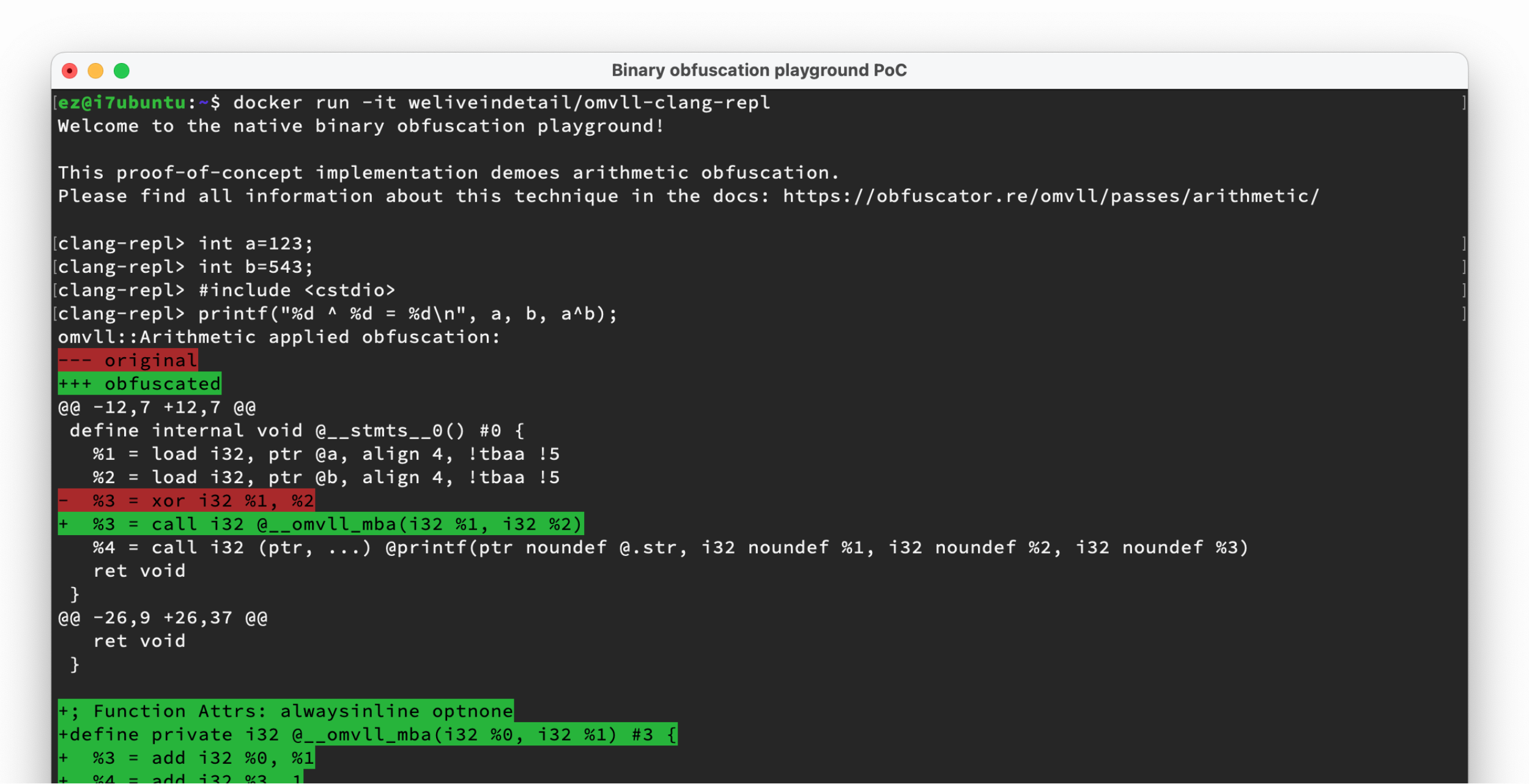

Interactive C++ with obfuscations

The outstanding benefit of the script-based approach is the ability to use it in tools that don’t write their outputs to files on disk! In particular, this is interesting for clang-repl, the interactive C++ interpreter in upstream LLVM. It uses the clang frontend internally and supports the same options (with a -Xcc prefix), including -fpass-plugin:

➜ clang-repl -Xcc -O1 -Xcc -fpass-plugin=/path/to/libOMVLL.so

clang-repl> #include <cstdio>

clang-repl> int a = 1;

clang-repl> printf("%d\n", a^123);

omvll::Arithmetic applied obfuscation:

--- original

+++ obfuscated

@@ -11,8 +11,8 @@

define internal void @__stmts__0() #0 {

entry:

%0 = load i32, ptr @a, align 4, !tbaa !5

- %xor = xor i32 %0, 123

- %call = call i32 (ptr, ...) @printf(ptr noundef @.str, i32 noundef %xor)

+ %1 = call i32 @__omvll_mba(i32 %0, i32 123)

+ %call = call i32 (ptr, ...) @printf(ptr noundef @.str, i32 noundef %1)

ret void

}

@@ -26,9 +26,38 @@

ret void

}

+; Function Attrs: alwaysinline optnone

+define private i32 @__omvll_mba(i32 %0, i32 %1) #3 {

+entry:

+ %2 = add i32 %0, %1

+ %3 = add i32 %2, 1

+ %4 = xor i32 %0, -1

+ %5 = xor i32 %1, -1

+ %6 = or i32 %4, %5

+ %7 = add i32 %3, %6

+ %8 = or i32 %0, %1

+ %9 = add i32 %0, %1

+ %10 = or i32 %0, %1

+ %11 = sub i32 %9, %10

+ %12 = and i32 %0, %1

+ %13 = sub i32 0, %11

+ %14 = xor i32 %7, %13

+ %15 = sub i32 0, %11

+ %16 = and i32 %7, %15

+ %17 = mul i32 2, %16

+ %18 = add i32 %14, %17

+ %19 = sub i32 %7, %11

+ %20 = or i32 %0, %1

+ %21 = and i32 %0, %1

+ %22 = sub i32 %20, %21

+ %23 = xor i32 %0, %1

+ ret i32 %18

+}

+

attributes #0 = { "min-legal-vector-width"="0" }

attributes #1 = { nofree nounwind "no-trapping-math"="true" "stack-protector-buffer-size"="8" "target-cpu"="x86-64" "target-features"="+cmov,+cx8,+fxsr,+mmx,+sse,+sse2,+x87" "tune-cpu"="generic" }

attributes #2 = { uwtable "min-legal-vector-width"="0" "no-trapping-math"="true" "stack-protector-buffer-size"="8" "target-cpu"="x86-64" "target-features"="+cmov,+cx8,+fxsr,+mmx,+sse,+sse2,+x87" "tune-cpu"="generic" }

+attributes #3 = { alwaysinline optnone }

!llvm.module.flags = !{!0, !1, !2, !3}

!llvm.ident = !{!4}

122

clang-repl>

Limitations in the PoC

Pass implementations in OMVLL use LLVM’s bare C++ interfaces, so that the version it links must match the one in the target compiler exactly. O-MVLL was built for LLVM 14 and just recently moved on to LLVM 16. clang-repl is still under development and works best with very recent versions of LLVM.

For the proof-of-concept in this post, I had to do a partial upgrade of O-MVLL to LLVM 18. It’s just enough to run the demo, so please don’t expect other obfuscation passes to work yet.

Conclusions and future work

In the race between protection techniques and reverse engineering, the accessibility of tools for exploration plays a crucial role. This PoC might inspire some form of obfuscation workbench. My Docker image is probably not the ideal distribution method. (It was the fastest for sure!) Jupyter notebooks provide a much better user experience and they are very popular in scientific communities. xeus-clang-repl is a Jupyter implementation for C++ with Python interop and might serve as a basis.

O-MVLL provides a nice framework for exploring obfuscation techniques. The extensible Python API is flexible and powerful. However, I imagine that tinkering with O-MVLL is still difficult for security experts. We have to implement obfuscations in C++ and build the plugin from source. The plugin shared library and the target compiler must be ABI-compatible. This is very easy to break and quite complicated to debug. The version locking is likely to remain an issue for the foreseeable future. We can use the prebuilt deps packages from the upstream CI, but this limits us to the target compilers supported on current mainline (Android NDK r26d and Xcode 15.2 at the time of writing this post).

Another way to solve the build problem seems interesting: Why not extend the script API in a way that allows implementing entire obfuscations in Python? For performance reasons, it’s certainly not suitable for use in production, but for experimentation that seems acceptable. It could reuse existing bindings like Numba’s llvmlite. Key requirements are indeed similar: “Numba and many JIT compilers do not need a full LLVM API. Only the IR builder, optimizer, and JIT compiler APIs are necessary. The IR builder is pure Python code and decoupled from LLVM’s frequently-changing C++ APIs.”

Thanks for reading! Please ping me, if any of this triggers your interest!